Simulations of a room-temperature ionic liquid

Formerly known as "Tutorial: A room-temperature ionic liquid"

By Chris Lim and David A Case

The purpose of this document is to instruct the user in simulating ionic liquids at room temperature and calculating Radial Distribution Functions (RDFs) through the use of Amber, AmberTools and VMD.

Room-temperature ionic liquids are, as the name suggests, salts that exist in liquid states at room temperature. RTILs are of great interest to a variety of fields because they exhibit unique physical and thermodynamic properties, such as negligble vapor pressure, high thermal stability, high electrochemical stability, and low flammability. Moreover, ionic liquids exhibit high conductivity and a wide electrochemical window, which means that they are neither easily oxidized nor reduced, hence they are excellent candidates for efficient and green electrolytes in batteries. Due to the various potential applications RTILs promise, computer simulations of RTILs have widely propagated, and various combinations of different cations and anions have been designed and tested to further increase our knowledge in this field.

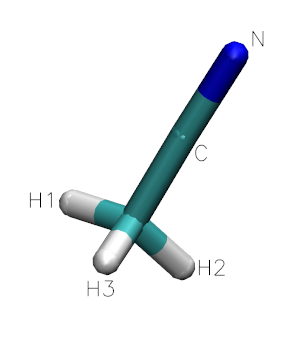

In this tutorial, we will be generating an ionic liquid mixture of 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate ([bmim][BF4]) and Acetonitrile (CH3CN) to replicate the data in the paper: X. Wu, Z. Liu, S. Huang and W. Wang, “Molecular dynamics simulation of room-temperature ionic liquid mixture of [bmim][BF4] and acetonitrile by a refined force field”, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 7, 2771-2779 (2005). See also Z. Liu, S. Huang and W. Wang, “A refined force field for molecular simulation of imidazolium-based ionic liquids”, J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 12978-12989 (2004).

Please note: this tutorial uses the general Amber force field (GAFF) force field to create an initial (not a “refined”) force field. Some aspects of the simulation results are not in as good agreement with experiment as the results presented in the papers listed above. This is a good object lesson: GAFF can get you started, and can provide results of reasonable accuracy. Depending on your needs, this may be enough. But it is often desirable to treat the GAFF results as a starting point for further refinement; the latter is usually system-specific, and is not covered in this tutorial.

1 Creating initial structures

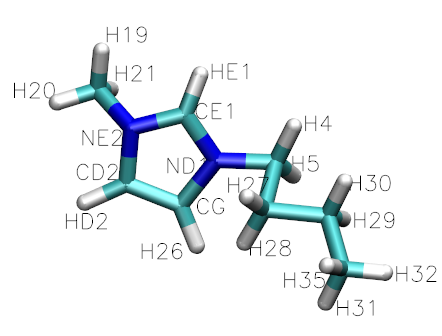

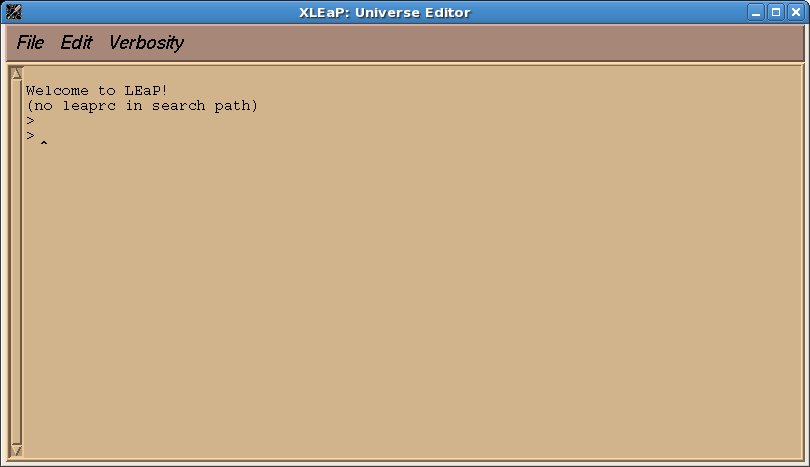

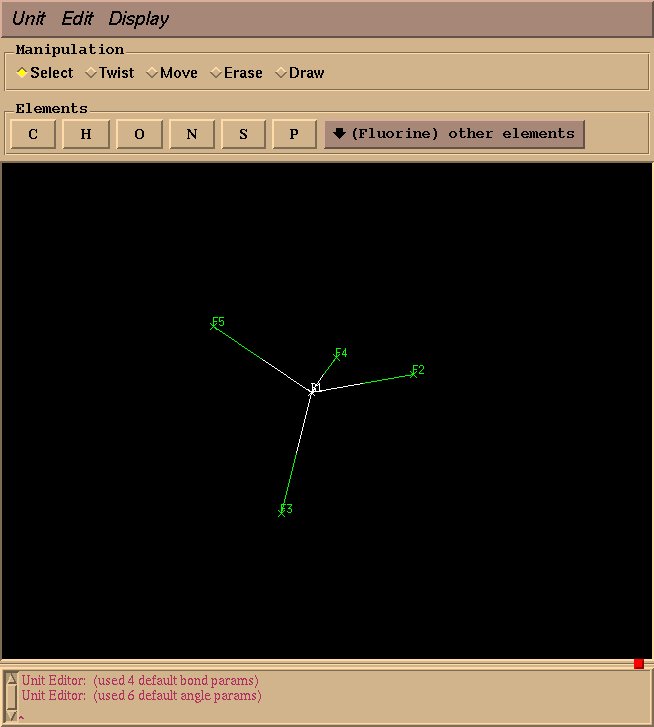

1.1 Drawing the molecules using xleap

We will use xleap to draw the molecules and to generate pdb files. First type “xleap” at the command prompt to bring up a window like this one:

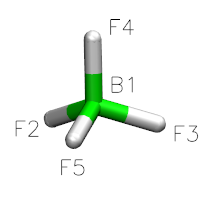

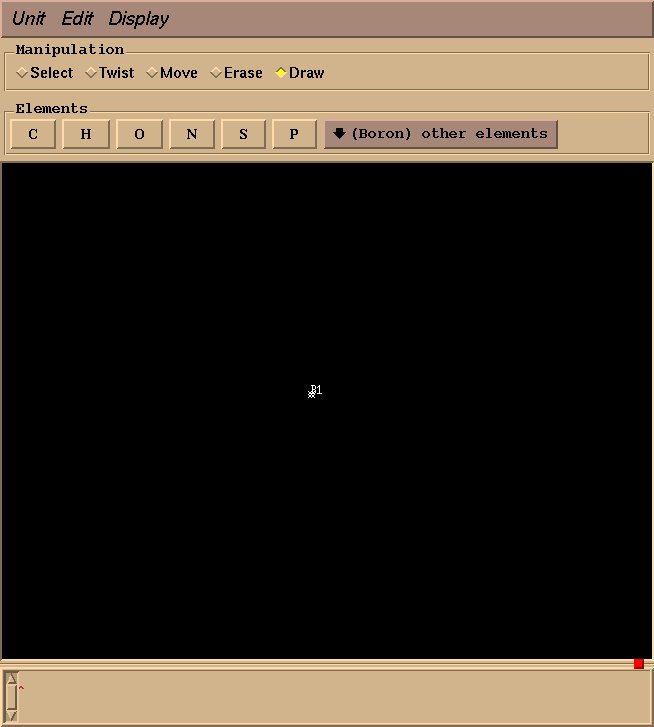

This will create an “BF4” object, and a graphical interface will open pop up. Drawing a molecule is fairly intuitive: select “draw” in the “Manipulation” box, select an appropriate element, click to draw an atom, and drag to draw a bond. For BF4, select “Boron” from “other elements,” and left click to draw a single boron atom.

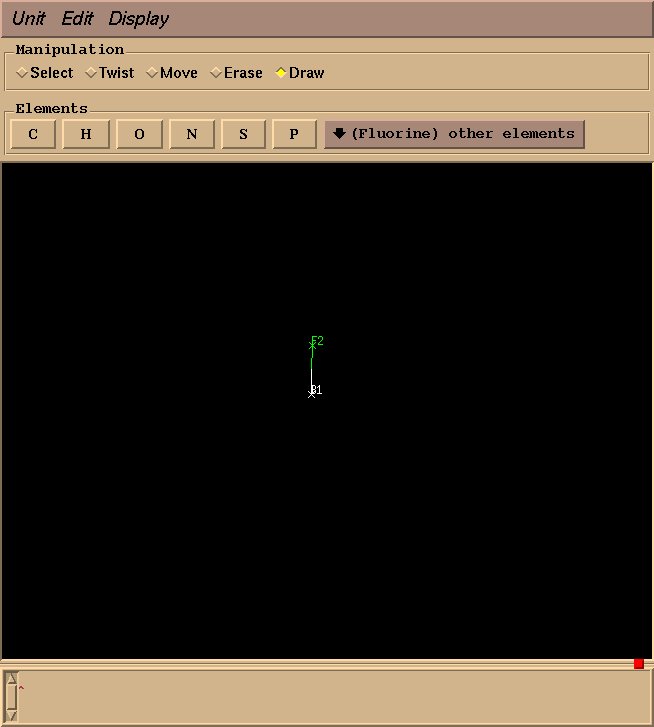

Next, select “Fluorine” from “other elements,” and drag your mouse from the boron atom to the desired fluorine position.

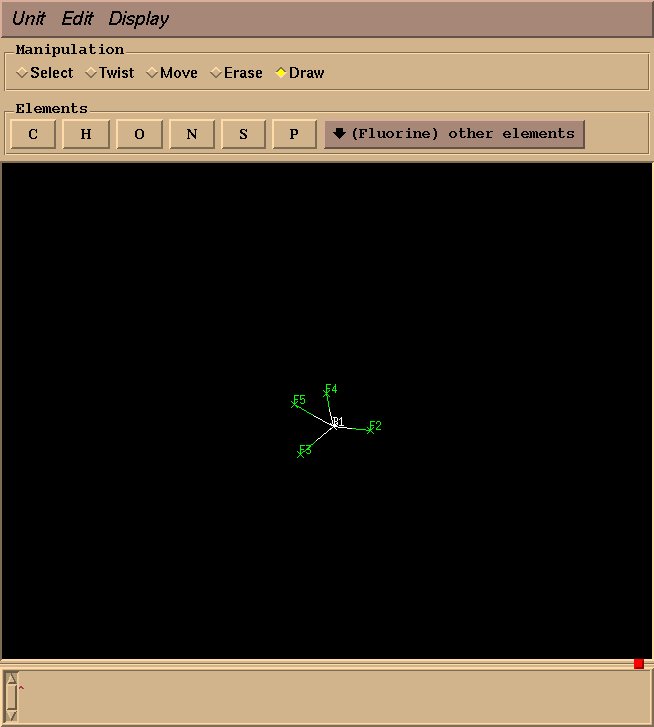

Draw three more fluorine atoms in the same manner, roughly in a tetrahedral geometry. The geometry need not be perfect at this stage–rough estimations will suffice.

Note: Hold control and move the mouse to rotate the view. Hold control and the right mouse while moving the mouse upwards to zoom in or downwards to zoom out. If you click an atom and select it, hold shift and click anywhere in the drawing space to deselect.

Xleap will optimise the geometry for us. Select all atoms by dragging your mouse over the molecule (or by clicking each atom). Select “Relax selection” under the “Edit” menu.

Exit out of this window. Note: Do NOT use the “X” button, as xleap will quit in entirety and your work will not be saved. Instead, select “Close” under unit.

1.2 Creating a pdb file

1.3 Repeat

2 Antechamber

2.1 Generate mol2 and frcmod files for the Acetonitrile:

The mol2 contains charge information to be used in LeaP. The following commands will create a mol2 files from the pdb files:

To create the pdb file for our molecule, type in the following command: used in LeaP. The following commands will create a mol2 files from the pdb files:

(-i is input, -fi is input format, -o is output, -fo is output format, -c is charge method, and -nc is net molecular charge. Don't forget to use “-nc 1” or “-nc -1” for cations and anions, respectively.)

2.2 Problems with boron

Antechamber does not recognize boron, so we'll need to enter in the parameters ourselves. Our reference paper contains charges for each atom, so we'll use these numbers.

2.2.1 Run antechamber without the charge model

2.2.2 Edit the mol2 file

Using your preferred text editor (e.g., vim or gedit), open bf4.mol2. We'll need to make few changes:

First, if the second digit in the third line of the file is a “0,” change it to 4. This means that our molecule will have four bonds (four fluorines bonded to boron).

Second, locate the last column in the “Atoms” category. These numbers represent each atom's charge. As of now, they're all zeros since we didn't identify a charge model. Correct the charges by replacing this column with the numbers provided in the paper. (Boron: 1.1504, Fluorine: -0.5376).

Finally, we'll need to add in the bonds manually. Bonds are specified by the bond id, two atom numbers (the first column in the atom section), and the bond type (1 for single bond, 2 for double bond, etc.)

This would be the first record (the first number) that says that the B1 atom (the second number) and the F2 atom (the third number) will form a single bond (the fourth number).

2.3 Next, go to xLEaP and put in:

Generate mol2 files for bmim and BF4 by using antechamber and substituting input and output names with appropriate names. Repeat steps 1 and 2 for each molecule. You can get the mol2 files we created here: acn.mol2, bmi.mol2, and bf4.mol2. Compare them to the ones you have created.

3 Parmchk

Parmchk creates force field modification (frcmod) files that fill in missing parameters. The following command creates a frcmod file from the previously created mol2 file:

Repeat this step for the two remaining mol2 files. You can get the frcmod files we created here: frcmod.acn, frcmod.bmi, and frcmod.bf4. Compare them to the ones you have created. Note that the frcmod.acn file is essentially empty, since all of the parameters needed for that molecule were present in the gaff.dat file. You can get rid of this file if you want.

4 Packmol

“Packmol creates an initial point for molecular dynamics simulations by packing molecules in defined regions of space. The packing guarantees that short range repulsive interactions do not disrupt the simulations”.

- Download Packmol from http://www.ime.unicamp.br/~martinez/packmol/ and follow the installation instructions.

-

Create an input file named input.inp. Here is an example:

- Run Packmol

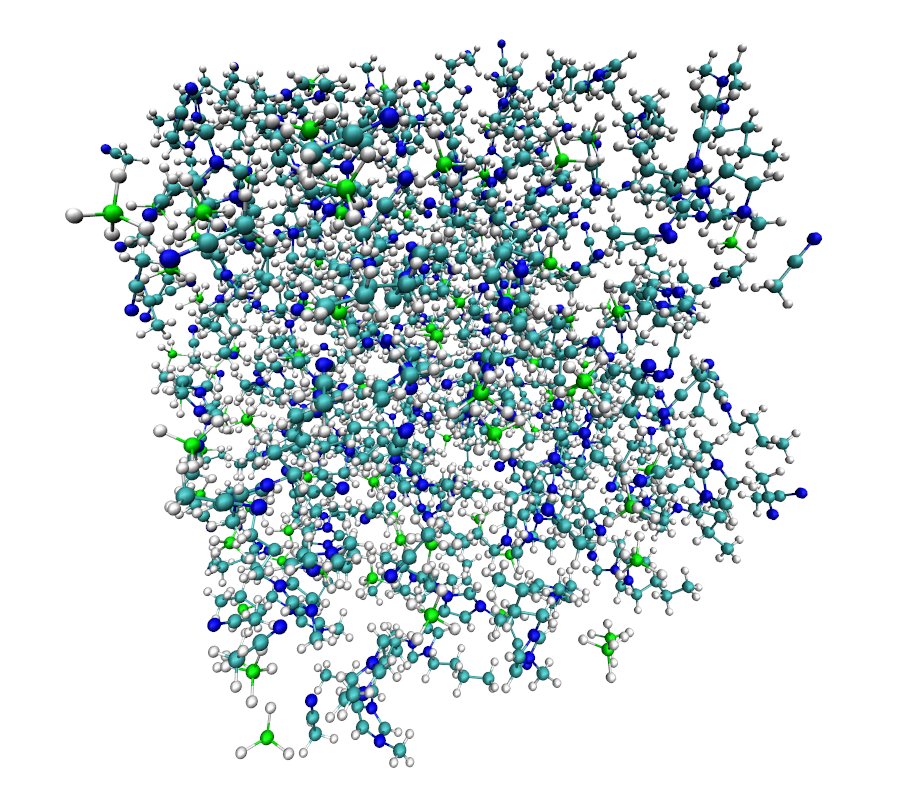

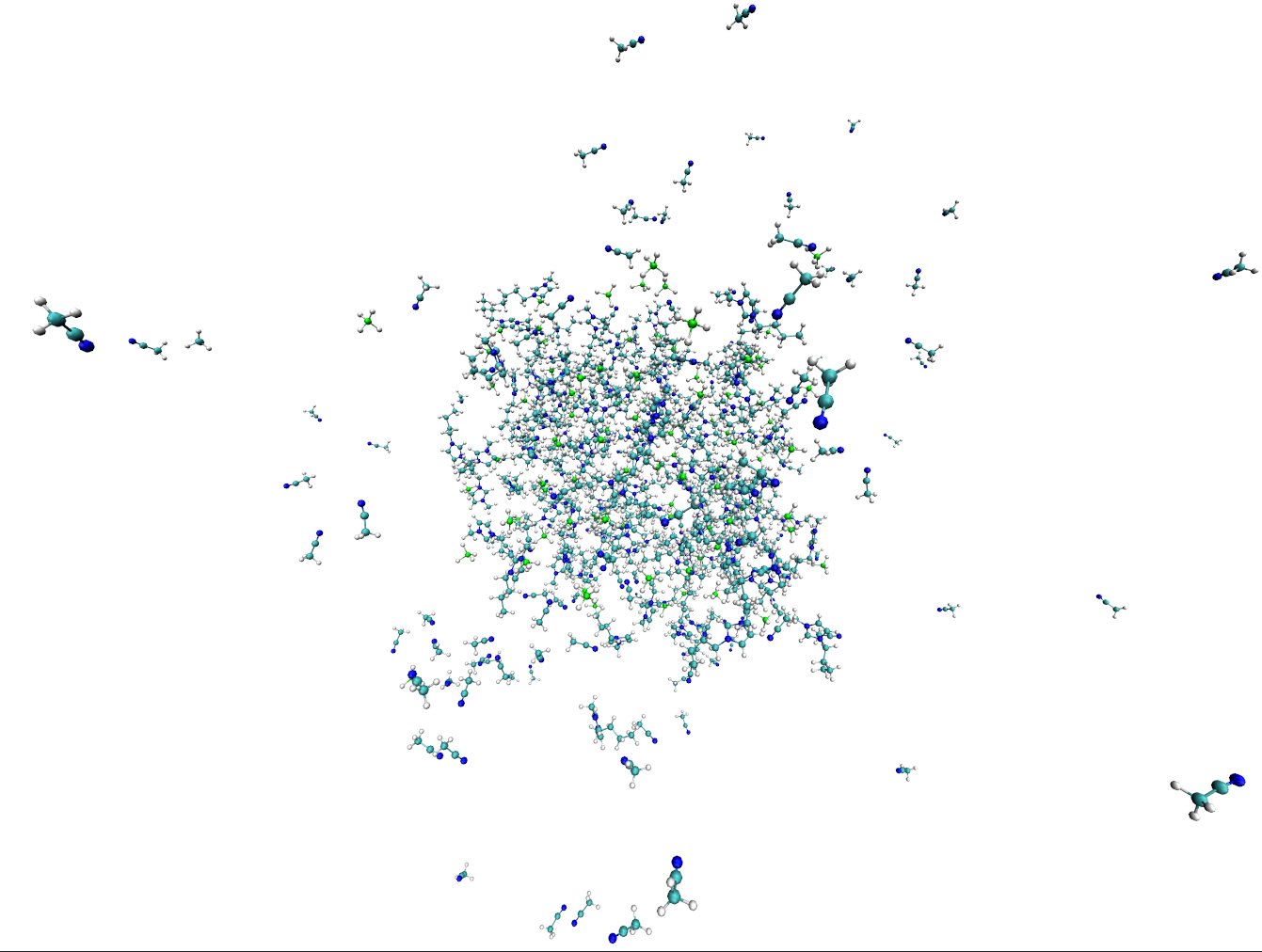

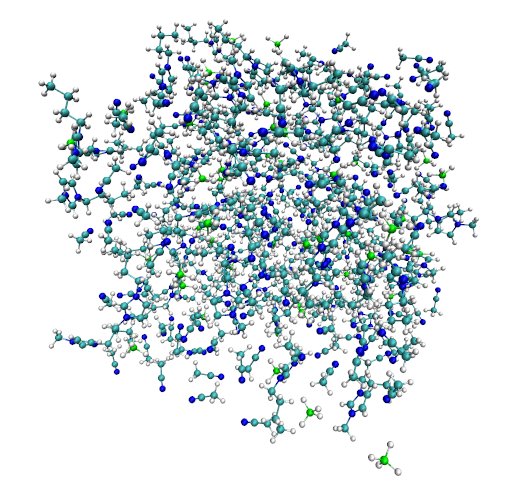

- View the pdb file generated by packmol in Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD):

5 Using tLEaP to generate Amber prmtop file

With the newly synthesized pdb file from packmol, use tLEaP to generate a parameter-topology file (prmtop) and a coordinates file (inpcrd).

6 Performing minimization with Sander

-

Create a script named runmin.sh. This script will create the input file and run sander. “imin=1” tells sander to run minimization, “ntpr=100” saves the restart file every 100 steps, “ntwx=100” prints the trajectory every 100 steps, “maxcyc=10000” runs minimization for 10000 cycles, and “ntb=1” specifies periodic boundary conditions.

- Note: Make sure you modify the arguments for sander if you want to run a second simulation. For example, after “min1” finishes, the input coordinate file should be “min1.x”, and the other output files should begin with “min2”.

7 Running Molecular Dynamics

Once again, you should look at the Amber manual to understand what exactly this input file is doing.

Note: The restart file generated from MD simluations contains velocity information that the restart file from minimization did not have. To address this difference, use ntx=5 and irest=1 for future simulations to denote that the restart file (that is, the new input coordinates file) indeed contains the velocity information for sander to process.

Also note: when you run the next simulation, use the restart file from the previous output as your new input coordinates file.

8 Imaging with ptraj

The box we created with packmol manifests a fundamental problem: a significant portion of the molecules is exposed to vacuum, which would yield deviations in simulation results. Under periodic boundaries, our box is “replicated” in all three dimensions so that our system represents a realistic bulk fluid. As a result, when a molecule exits the box from one side, it enters from the other. Ptraj's imaging tool repacks the molecules that left the box and gives us a proper image of what the central box looks like.

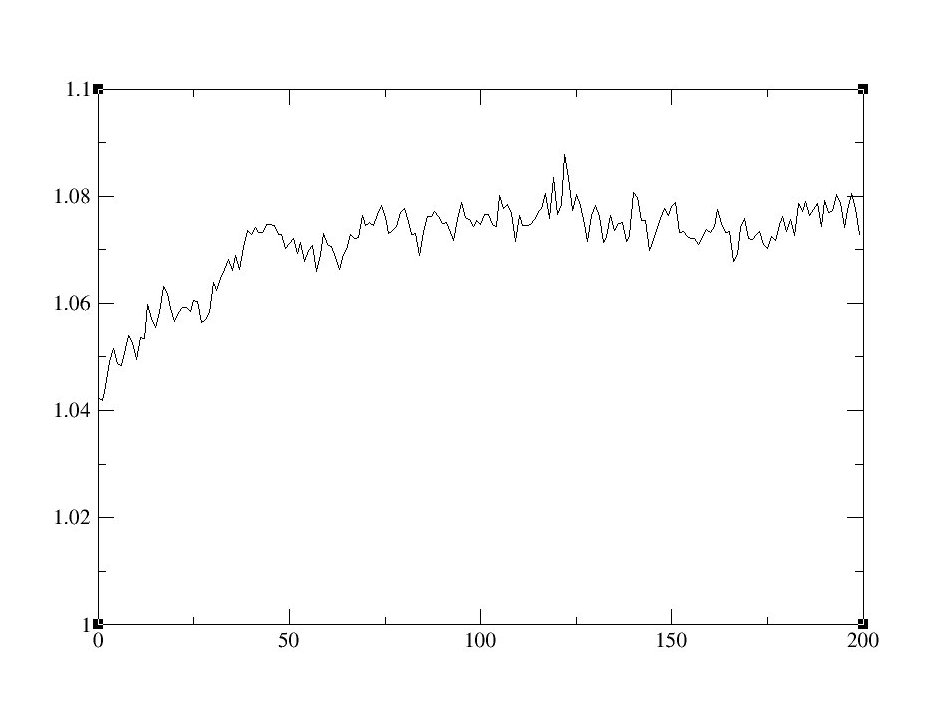

- First, analyze the Density to see if the average density is close to your target.

- To graph density data with xmgrace:

- To calculate the average density, examine the sets in xmgrace, or run the following script:

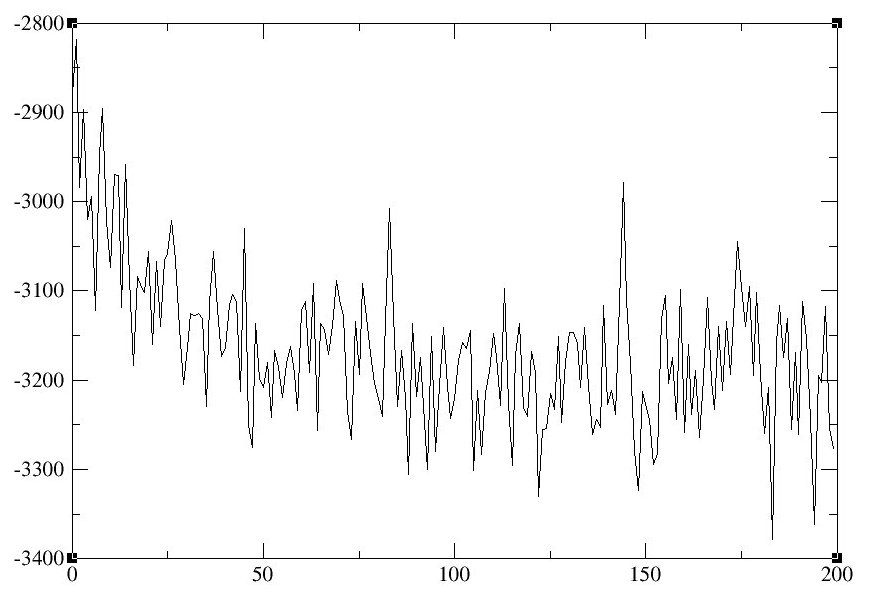

- Examine the Energy Total to see if the system is at equilibrium.

- Once the density is at target and total energy is at equilibrium, calculate Radial Distribution Functions.

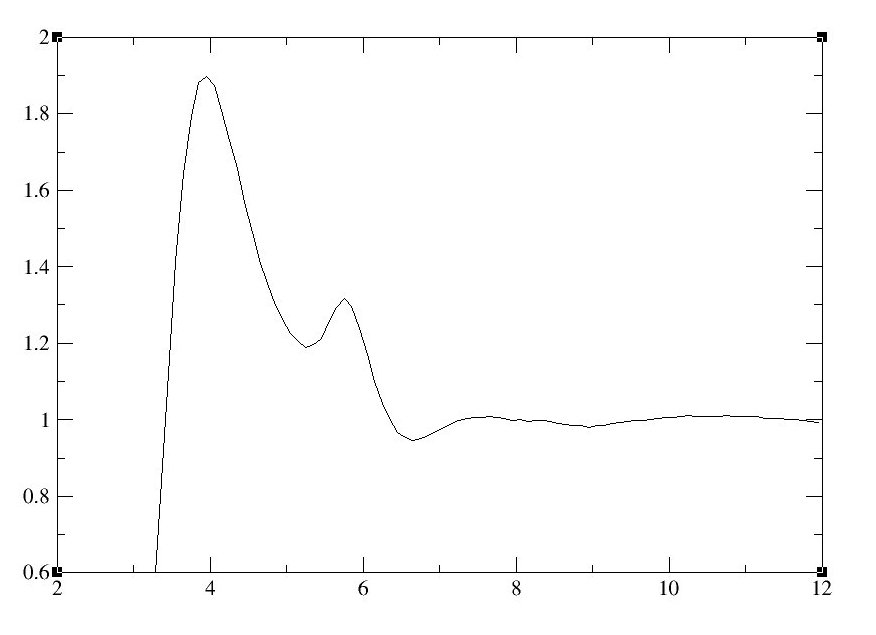

In order to calculate the RDFs, we will use ptraj, a program used to analyze sets of 3-D coordinates from input coordinate files. We will be calculating the RDF between the N1 atoms of the Acetonitrile [CH3CN]

CH3CN_N1 is the header for output file names, .1 is the bin size, 15.0 is the maximum for the histogram, and :ACN@N is the mask for selecting atoms we want to use for our analysis.

The output files that result after running the ptraj.in file will be: CH3CN_N1_carnal.xmgr CH3CN_N1_standard.xmgr CH3CN_N1_volume.xmgr

The above command will open the file CH3CN_N1_volume.xmgr in xmgrace. The x axis is distance in angstroms, and g(r) gives the probablity of finding an atom (in this case, the nitrogen in acetonitrile) at a given distance (r) of another atom (another nitrogen in acetonitrile). The first peak (around four angstroms) represents the first coordination shell, and the second peak (little less than six angstroms) represents the second coordination shell.

9 Self-Diffusion Coefficients

According to the Einstein relation, the self-diffusion coefficient D can be computed by using the equation below:

In order to calculate D, we will 1) Graph the averaged MSD over time using ptraj and gnuplot, 2) Find the slope of the graph, and finally 3) Plug the information into the equation to get D.

9.1 Create the input file

mask is the selection of molecules for analysis. For instance, if you want to calculate D for acetonitrile, replace “mask” with “:ACN”. To calculate D for all residues (which is what this tutorial does), use “:*”.

timestep is dt * ntwx, which gives you the time intervals inbetween entrees in the trajectory (in picoseconds).

9.2 Run ptraj

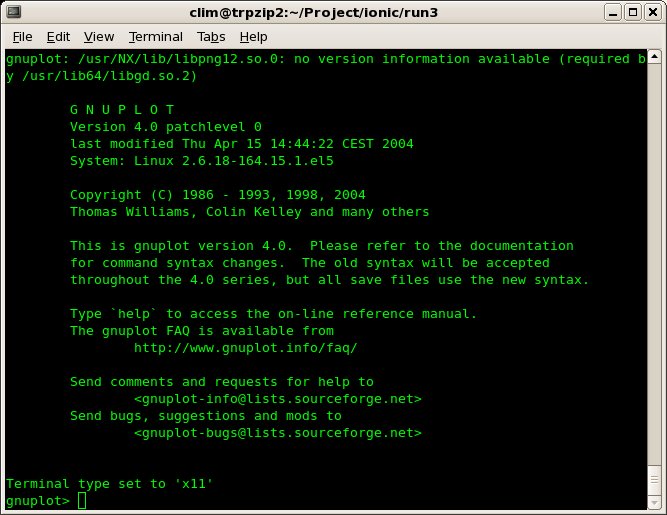

9.3 Run gnuplot

Open gnuplot (type in gnuplot in the shell). You should see “>” on the left, which means we're ready to run gnuplot commands.

9.4 Calculate

Using the graph as a reference, calculate the slope of the graph and plug the information into the equation. The units of the slope are angstroms squared over picoseconds.

Note: though the equation suggests that the slope near the end of the graph should be taken, ptraj's diffusion tool is most accurate at the beginning of the graph. This is somewhat apparent, as noise seems to increase as x increases.

Also note: The thermostat and barostat may disrupt the diffusion coefficient. To get more accurate measurements, run another simulation with the thermostat and barostat turned off.

In this case, the slope is 0.0635990 angstroms squared over picoseconds, or 63.5990 * 10mover seconds (the units our reference paper uses). To find the diffusion coefficient, we need to divide this number by six, which gives us 10.5998 * 10mover seconds. In comparison, the reference paper's diffusion constant is 14.9 * 10mover seconds. A possible explanation for the difference is that our molecules use general Amber force fields, whereas the paper uses refined force fields.

10 Conclusion

We simulated a room temperature ionic liquid starting from scratch by “hand-drawing” the molecules with xleap, optimizing the geometry with antechamber, generating the topology and coordinates file with xleap/tleap, and running minimization and MD simulations with sander. We also used ptraj to perform analyses on the data we collected, such as calculating RDFs and self-diffusion coefficients, and we used xmgrace and gnuplot to aid us in visualizing the data. Hopefully, by the end of this tutorial, you'll feel more comfortable with the numerous tools the AMBER suite provides, and you can now move on to more complex simulations (and more complex analyses!).